Exhibition

- Neilma Sidney Theatre

- April 25 - June 9

- Tues - Sun | 12 - 6pm

- Opening Reception: April 25 | 6:30pm - 8:30pm (Free with RSVP)

Free

Beatriz Cortez and Candice Lin is an exhibition of works by two artists, who have long been in conversation with one another, both challenging viewers to see non-human objects through the lens of performance and to consider objects as beings with agency. The works in this exhibition engage matter loaded with histories of colonialism and migration; matter whose significance reverberates across time and space. “The performance of matter, and the experiences of simultaneity that it brings with it, is something beyond the human,” says Cortez. Relatedly, Lin asserts, “…the work becomes centered on the bodily relationships we have towards material and the things it makes us do.”

Cortez’s two works, The Time Machine and The Fortune Teller, are interactive, and visitors are invited to engage with them. Cortez’s works create portals that evoke immigrant experiences of yearning and simultaneity: living in one place but inhabiting the reality of an origin city — the constant overlap of disparate times and locations in a person’s life.

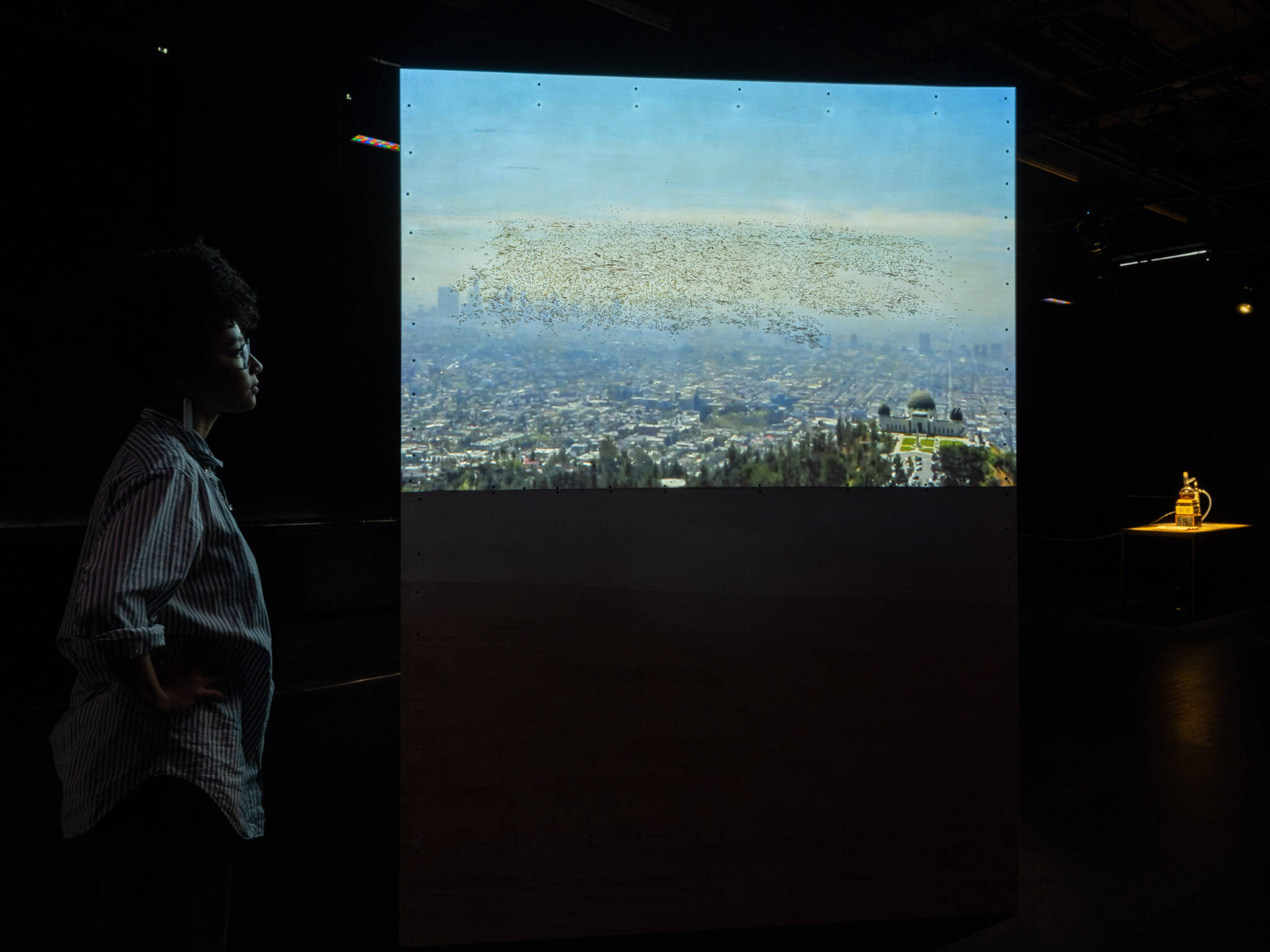

The Time Machine is an installation that explores the entwinement of two urban spaces separated by 2,301 miles. Los Angeles and San Salvador have strong connections to one another through labor and culture, with Los Angeles being home to the largest Salvadoran population outside of San Salvador; the two were formally named so-called ‘sister cities’ in 2005.

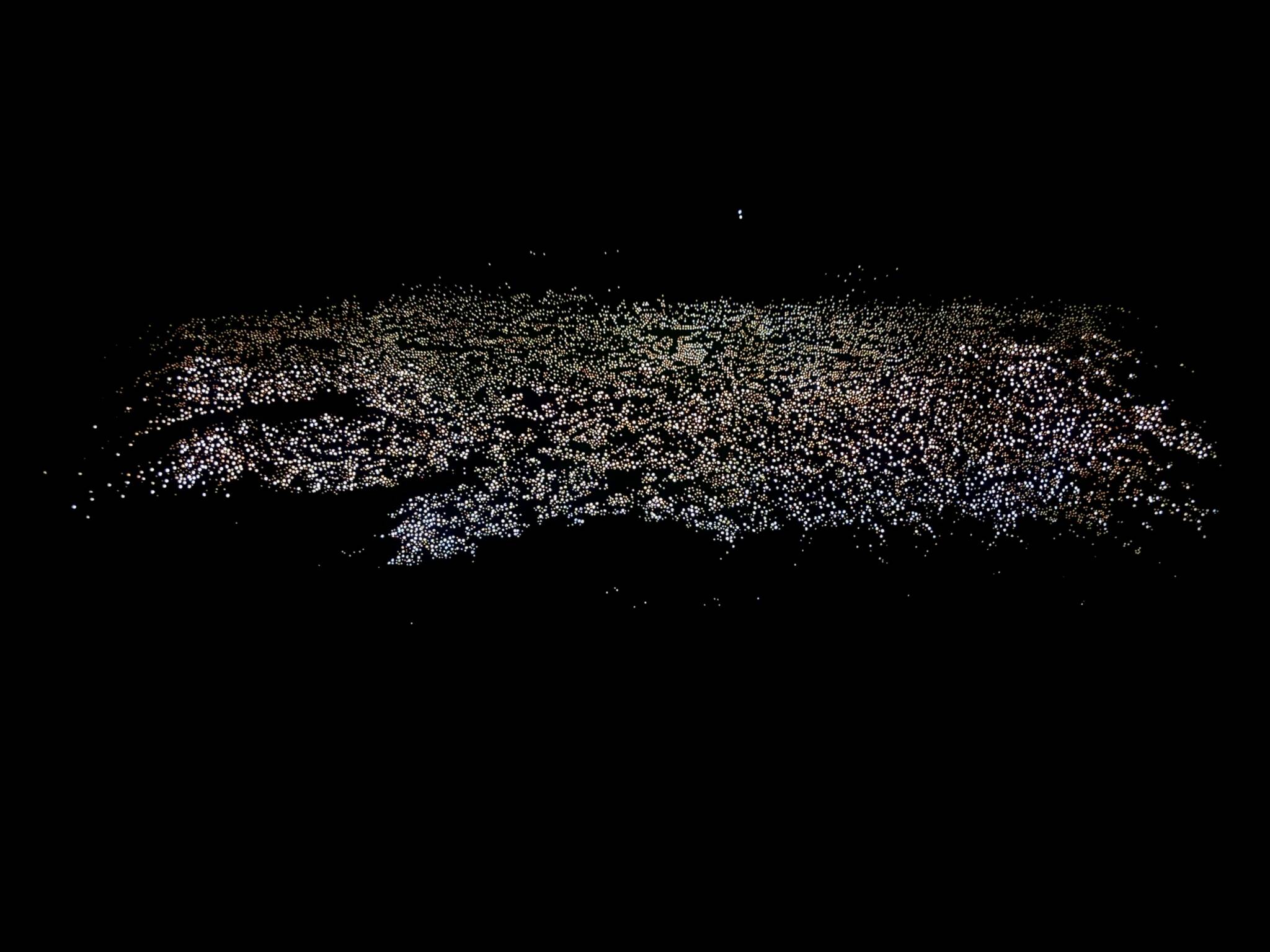

A video projection of Los Angeles in the daylight shines on one of the exterior walls of a large wooden box, while the inner space is dark. The light from the video permeates holes drilled into the wall dividing the installation’s outside and interior—creating in the light-dotted dark space a precarious video projection of a distant view of San Salvador at night. Inside, the viewer can sit on a swing reminiscent of childhood, and sway as the lights blink in playful suspended reflection.

The Fortune Teller quotes desires for the future uttered by immigrants and border crossers, which flow out in the form of paper tickets generated by Arduino programming inside the box. With this work, Cortez seeks to enable conversations between people who are not in the same place and time, extending lives through language, and beyond the confines of the human lifespan.

Breaking the barriers that separate lives and histories, The Fortune Teller also opens up the possibility for others, who are yet unborn, to enter into conversation with those who have passed away, whose bodies are gone. The material fragments of those lives—like words on paper—remain.

Candice Lin’s multi-part installation, On Being Human (The Slow Erosion of a Hard White Body), traces the materialist histories of colonial goods such as indigo, opium, sugar, porcelain, and tea. Lin examines the entangled connections between these products and the racialized language around their dispersal and value.

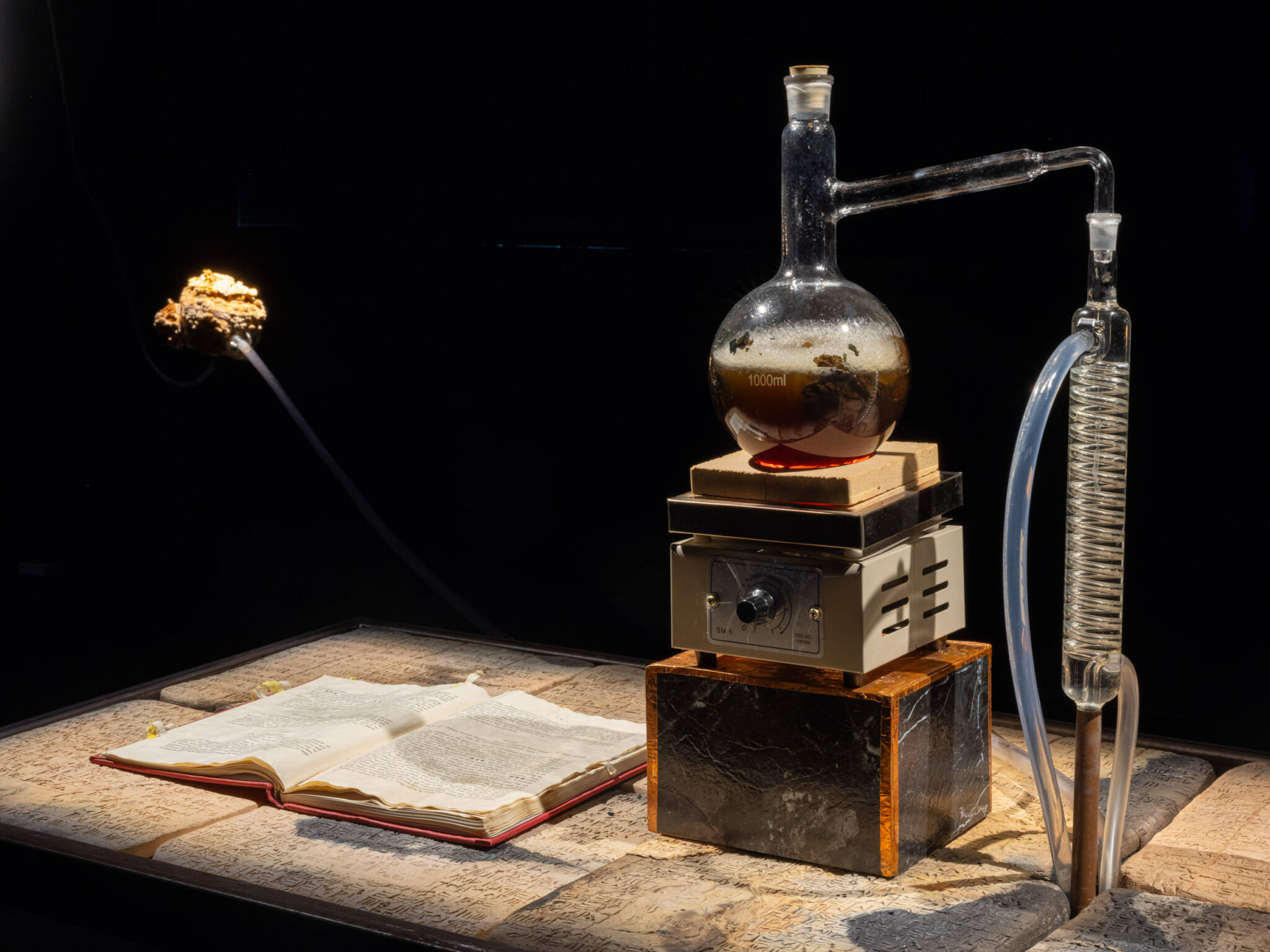

The installation comprises a table tiled with clay tablets as well as a distillation and pumping system that distributes liquid through an arrangement of tubing and buckets, emptying onto a large wooden structure. The clay tablets are inscribed with stamped text that looks like cuneiform but is actually English, displaying a passage from John Searle’s 1980 essay Minds, Brains, and Programs. The essay uses the metaphor of a “Chinese Room” to determine “a human level of consciousness” and is premised on Western misconceptions of the foreignness and inscrutability of the Chinese language. On top of this table, the distillation system boils a dark brown mixture of plants—dried poppies, tobacco, indigo, tea, sugarcane—echoing the global circulation of goods and forced migration of indentured Chinese workers in the 19th century.

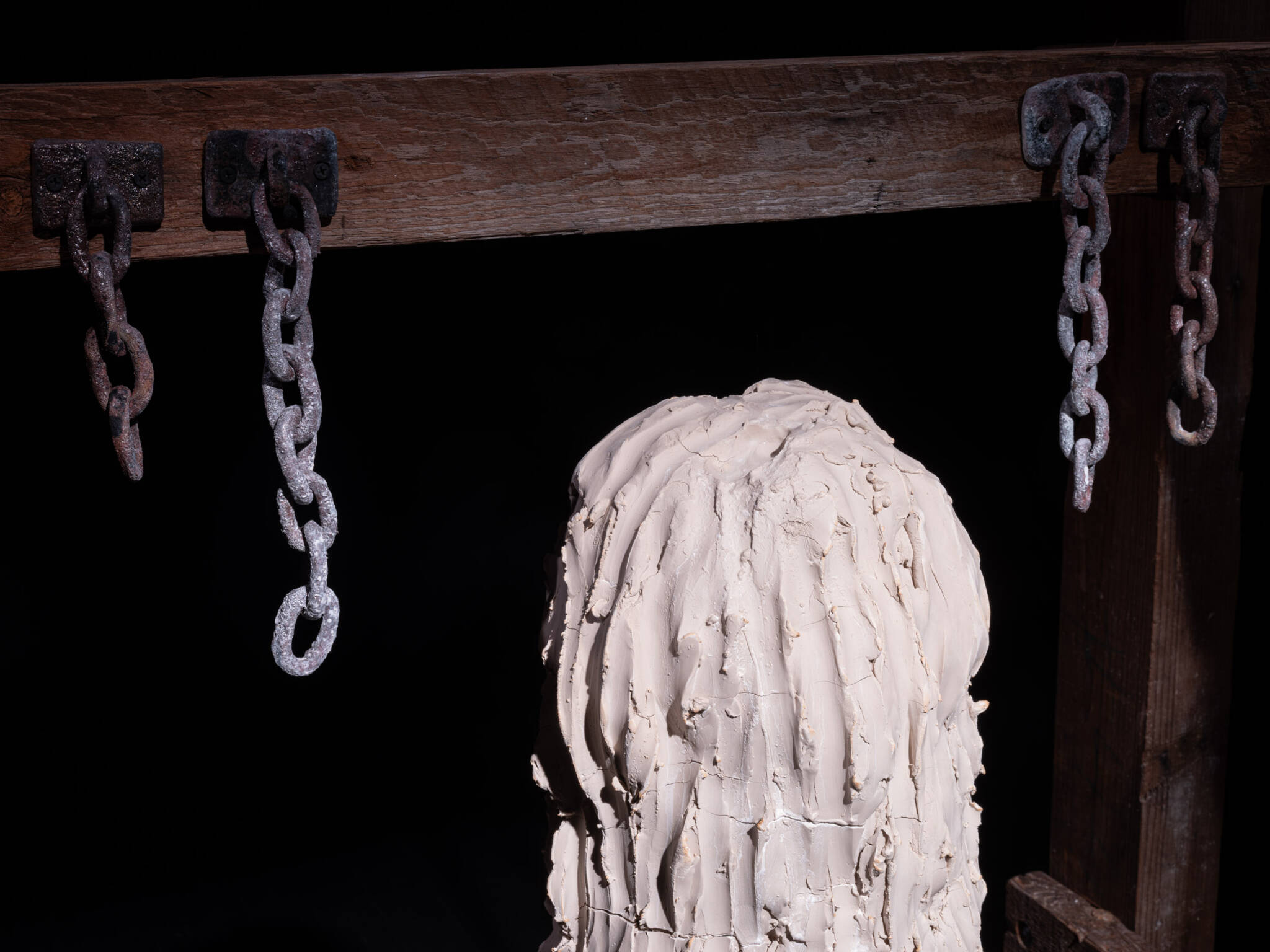

Imbricated in plantation economies, these plants also served as poisons or medicines for acts of resistance. The concentrated distillate ends its cycle by dripping into a ceramic bucket on top of a wooden structure modeled after a nineteenth-century torture device used in U.S. prisons (which was racialized by the name “Chinese Water Torture”). The unrelenting drops slowly erode a block of unfired porcelain—which is the same weight as the artist—sitting on the wood structure.

Using archaic forms of early record-keeping, such as clay tablets, the exhibition expands contemporary notions of research by revisiting these loaded materials and revealing stories that are left out of these early historical records. By setting these materials into circulatory, fluid, seeping, entropic relations with one another, the installation seeks to create new orientations, stories, and ways of being.

Photo by Young Chung

Photo by Kris Graves

Photo by Kris Graves

Photo by Kris Graves

Photo by Kris Graves

Photo by Kris Graves

Photo by Kris Graves

Photo by Kris Graves

Photo by Kris Graves

Photo by Kris Graves

Photo by Kris Graves

Photo by Kris Graves

Photo by Kris Graves

Photo by Kris Graves